Tree and Well

The Logo and Credo of Metahistory

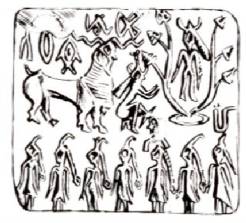

Over the millennia human imagination in many cultures has pictured a cosmic tree growing from a sacred well. A cylinder-seal from the Indus Valley (dated around 2200 BC) represents the adoration of the Goddess who indwells the Tree. Kneeling before Her is the shaman in horned attire, the ancestral Hunter who represents one aspect of the primordial religious orientation of the human species: awe in the presence of the animating powers of Sacred Nature. The conical buds at the ends of the limbs of the Sacred Tree are notably mushroom-like. The flattened circle at the root of the Tree represents the Well.

Ascent and Descent

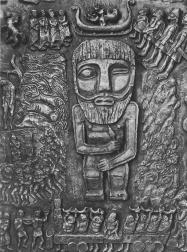

Nordic

mythology presents the same eternal image in the story of the

poet-shaman Odin (or Woden), who must hang on the cosmic tree for nine

days and nine nights

to receive a sublime revelation. He ascends the Tree to surrender

to the streaming of cosmic currents through its leaves and branches.

Through this ordeal he acquires the runes, a secret alphabet

composed of divinatory symbols. The runes represent the generative

formulas

of all possible languages, the bases of all verbal and written expressions

in which human knowledge can be captured and transmitted. By

his ordeal the "tree-hung" shaman acquires the magical power of language, but still needs

access to the transcendent wisdom that will use language for

its instrument.

For this second endowment, Odin must descend into the underworld,

to the root of the Tree, and drink from the miraculous Well of

Mimir. The name Mimir is related to the Latin memor, hence

Mimir’s Well has been called the “well of remembrance”.

Ralph Metzner explains:

The Metahistory logo shows a “well filled with stories” and the language- tree that grows from it represents the many-branched (multi-cultural, multi-racial) expression of those stories in verbal and written form.

Metahistory is “an

experience that involves both visioning and storytelling”,

and something more as well. Our capacity to be authentic, true-speaking

channels of the wisdom endowed in our species is hampered by

conditioning. For modern humanity, communion with Sacred Nature (the Goddess

in the Tree) has been overwritten by socialization: that is,

by education, by racial-political conditioning and, most

of

all, by centuries of religious indoctrination. Encumbered by

our cultural habits of thought and judgment, we cannot access

the life-giving

wellspring of ancestral memory. Our conditioning blocks

our capacity to draw upon the innermost resources of

our own species-specific biogenetic

matrix. Unable to realize the full benefit of our own intelligence,

we are reduced to following a set of behaviors that do not reflect

the true promise of human sapience.

This is

Jeanette Armstrong, Okanagan author, artist and bioregional activist,

in conversation

with Derrick Jensen (Listening to the Land, p. 297ff.) She

explains that her indigenous group, the Okanagan of British Columbia,

have a

long-standing tradition called En’owkin. This involves a process of conflict resolution

in which all parties agree to put their views in question. “To be

a practitioner of En’owkin process,” Jeanette Armstrong says, “is

to constantly school myself in deconstruction of what I believe and

perceive to be the way things are, to continuously break down in my

mind what

I believe, and continuously add to my knowledge and understanding.”

This sentence could stand as the “mission statement” for

one aspect of Metahistory.org: metacritique, the radical analysis and deconstruction of beliefs.

Like En’owkin, the practice of metahistory involves quite

a lot of work in deconstruction and deconditioning. A process of

clearing distortion and countering disinformation is required,

so that we can gain free access to the innate knowing unique to

our species. We hear every day of events that “make history.” In

Metahistory we are often concerned with the opposite: unmaking

history, deconstructing the stories that do not reflect the sacred

endowment of our self-guiding powers.

The wisdom

by which we are linked to all other species, to the Earth and

the cosmos at large, dwells in poetic-visionary imagination,

but it

takes the self-effacement of the conditioned mind to release

our imaginative powers. “True knowledge is earned, through disciplined

learning; it is not given away” (Metzner, p. 155). Nordic

myth says that when Odin came to the Well of Mimir, he was confronted

with a test by its guardian. The giant demanded an act of surrender

before allowing Odin to drink at the Well. To gain illumination

by mystic memory, Odin must surrender one of his eyes. Hence

this shaman became known as the One-Eyed Seer.

The myth teaches that we must surrender our one-sided

way of seeing and understanding, the preclusive rational mentation

of the left brain, in order to realize the poetic-visionary

faculties of the other eye, the right brain awareness.

Curiously, the left-brain mentality, when surrendered, does

not go away. According

to the Icelandic Eddas, “when the giant Mimir, or other

gods of knowledge-seeking shamans, drank from the well, they

would see

Odin’s eye looking back at them.” (Metzner, ibid.)

Sunk to the bottom of the well, the sacrificed eye (the rational

faculty, Odin's left eye)

keeps seeing.

The myth teaches that we must surrender our one-sided

way of seeing and understanding, the preclusive rational mentation

of the left brain, in order to realize the poetic-visionary

faculties of the other eye, the right brain awareness.

Curiously, the left-brain mentality, when surrendered, does

not go away. According

to the Icelandic Eddas, “when the giant Mimir, or other

gods of knowledge-seeking shamans, drank from the well, they

would see

Odin’s eye looking back at them.” (Metzner, ibid.)

Sunk to the bottom of the well, the sacrificed eye (the rational

faculty, Odin's left eye)

keeps seeing.

At this point it would appear that the higher teaching of the

myth proposes an arresting thought: if we peer deeply enough

into

the well of ancestral wisdom, the rational, left-brain thinking

with which we are so identified and in which we invest the

sole validity for knowing how the world works, will be there

peering

back at us. Here the myth conveys a key

survival lesson: rationality is not precluded from the deep-level

transrational knowing of ancient seership, even though the

rational limits of cognition must be surpassed for that deeper

knowing

to become experiential. This paradox was uniquely understood

in the

tradition of the Gnostics, pagan spiritual teachers who asserted

the basic complementarity of rational and visionary knowledge.

The course of human experience over

the last 6000 years has seen a steady decline in human capacity

to access

the poetic-visionary resources represented by Tree and Well.

For reasons that are eminently difficult to understand, the

primordial wisdom preserved in bioregionally oriented shamanic

traditions

has degenerated, or been repressed. In its stead there has

arisen another religious orientation, a totalitarian and dogmatic

system

of beliefs represented mainly in the doctrines of the Abrahamic

creeds, Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

Why is modern culture all around the world dominated by stories

that do not reflect the genuine visionary wisdom needed to

guide humanity on its proper course of experience?

Somehow, in the millennial process by which we have become

alienated from our origins in Sacred Nature, religious ideology

has replaced

poetic-visionary wisdom as the directing narrative of our species.

Stories that mislead and harm us, diving humans against each other and leading us to destroy

ourselves and our habitat, have been imposed on the human race

by misguided

people who have introduced those stories to serve their selfish

ends, the acquisition of power and privilege, and the pretence

of divine, superhuman authority. Aggression for the sake of

power and acquisition has been asserted

as

the

highest form of human endeavor. Faith-based violence has been,

and continues to be, the dominant social shaping force in history.

The belief-systems that currently

dominate

the world are believed to originate from male sky gods who

sanction territorial aggression, genocide, control by violence

or threat

of violence, and wholesale destruction of the natural habitat.

By some accounts, the religious ideology that sanctions such

behavior

represents a pathological deviation for our species—quite

literally, a drift into insanity.

Almost everything in modern society encourages selfishness

and separation, pitting human beings against each other in

a Darwinian

struggle for survival. These behaviors are supported and sustained

by religious, scientific and cultural scenarios that reflect

an insatiable need to dominate and control. The dominant stories

of

our time are leading the human species toward discord and self-immolation.

We must wonder: How is it possible that the power of our original

knowing, the sacred endowment represented by Tree and Well,

could have been so overwhelmed by pathological tendencies?

If the primordial wisdom acquired by Odin really is innate,

so

essential

to who we are and how we fit into the great scheme of things,

how could it ever have been uprooted by anything that is manifestly

false and alien to our true path?

It seems inconceivable that such a turnaround could occur,

yet the evidence is irrefutable. The course of history in the

last

5000 years provides one example after another, and on-going

verification, if you need it, is amply provided each and every

day in the news.

One of the challenges of

Metahistory is to fathom the initial causes of species-specific

deviation and trace the trajectory of this terrible shift. Although

the problem is far from resolved, some insights have been developed

that hold up well under critical assessment. Katherine Keller,

a professor of theology at Drew University in New Jersey, has

developed a number of metahistorical insights on the problem

of human species

deviation:

We have no reason to believe that in all time life has been based on the dominance of the weaker by the stronger, nor do we have any evidence that people have always lived in the defensive state of being that characterizes modern life. . Within a group in which warrior males are coming to the fore and dominating the tribe or village, everyone in the village will begin to develop a sort of self that is different from that of earlier epochs, a self that reflects the defenses of the society itself configures . . .

Even today that’s what we see in situations where abuse communicates itself from one generation to the next. Over and over again we see the causing of pain — destructiveness and abuse — flowing out of a prior woundedness . . . Because the people who embody the defensive persona will dominate these societies, this kind of self-damaging and community-destroying and ecology-killing defensiveness tends to proliferate cancerously. (Interview with Derrick Jensen, op.cit., p. 273-4.)

If modern society on the global scale is driven by a system of domination rooted in an original abuse, “a prior woundedness,” then it would be most enlightening to know how that wounding occurred. Metahistory explores this daunting question from many angles.

In the Indus Valley, in Iceland, and in

many other places around the world, the shaman was the central

figure in the story of how ancestral wisdom is continually accessed

(descent into the Well) and renewed (ascent to cosmic consciousness,

expressed in the language of poetic-visionary discourse: the sacerd Tree). But that

is not all there is to the shaman’s tale. A secondary

and no less significant theme in shamanic lore concerns the

wounding

of the seer. Could this event in some way be connected with

the original wound (not original sin) to which Katherine Keller

and

others have pointed?

Joan

Halifax, a key revivalist of ancestral traditions, subtitled

her book on shamanism, “The Wounded Healer.” She

writes that

accounts of the shaman’s inner journey of turmoil and distress, sung and poeticized, condense personal symbolism through a mythological lens that encompasses wider human experience.” (p. 19)

Whatever happened to our visionary quest as a species that somehow affected a terrible shift in the course of human experience, can only be known by recovering the true story to describe that event. Theologian and ecophilosopher Thomas Berry insisted that we are living in a crucial moment of human evolution when it is necessary to ”re-invent the human at the species level.” (Cited in Metzner, ibid.) Such an act of re-invention is only possible by accessing the resources of original vision represented by Tree and Well.

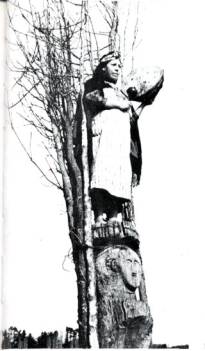

Until less than a century ago, the Indus Valley Goddess in the

Tree was still a living image, embodied and enacted. Visionary

powers were cultivated in bioregionally preserved shamanic practices

in various native-mind cultures around the world. The machi,

the shaman of the Mapuche region of Chile stands entranced in the

sacred tree beating her ceremonial drum. Here is the the Indus

Valley Goddess reflected in human form. (Photo in Halifax, p. 85)

This snippet of anthropological lore is evidence of a millennial continuity that now at risk of being ruptured in a final, devastating snap. Shamanic traditions are

dying out all over the world. In the 21st century we are seeing

the willful decimation of the small handful of remaining representatives

of this continuity.

Until less than a century ago, the Indus Valley Goddess in the

Tree was still a living image, embodied and enacted. Visionary

powers were cultivated in bioregionally preserved shamanic practices

in various native-mind cultures around the world. The machi,

the shaman of the Mapuche region of Chile stands entranced in the

sacred tree beating her ceremonial drum. Here is the the Indus

Valley Goddess reflected in human form. (Photo in Halifax, p. 85)

This snippet of anthropological lore is evidence of a millennial continuity that now at risk of being ruptured in a final, devastating snap. Shamanic traditions are

dying out all over the world. In the 21st century we are seeing

the willful decimation of the small handful of remaining representatives

of this continuity.

As I write these words, the San Bushmen of the Kalihari Desert

of South Africa have finally been removed from their habitat by

the agents of corporate development. Relocated to camps where they

cannot survive on the skills they have learned and preserved for

over 16,000 years, they are provided with processed food rations

and beer in two-liter cartons. The teenagers among them are already

wearing walkmans and catching Aids. A CNN reporter interviewed

one San tribeswoman who refuses to leave the land of her ancestors.

She is small and seemingly frail, as the Bushmen are by nature.

Her gentle face is taut, like a mask of excruciating, speechless

grief, but her eyes flash with ferocious defiance as she says in

halting English that she will not leave, she will not be removed

by force, she will die where she is rather than go to the relocation

camps.

Reflecting on Thomas Berry’s call for a species-specific myth

for our time, Ralph Metzner observes:

I take this to mean that the existing cultural paradigms cannot deal adequately with the issues we are now facing and that we need to draw upon the evolutionary wisdom of the human species in its interrelationships with all other species and ecosystems. The viability of the human species and its mode of adaptation to the natural world is now called into question. Indeed, we have brought conditions in the entire biospheric life system to a dangerous impasse. (Op.cit., p. 171-2)

In both its deconstructive and its imaginative features, Metahistory emphasizes the importance of story in the crucial reorientation of humanity toward a sane and sustainable way of life. “As space is to place, time is to story.” (Metzner, p. 183ff.) We are living stories in a double sense: we are living out (i.e., enacting) stories, and we are stories that live. All our individual stories are interwoven with the all-encompassing story of the human species, but we have lost the plot-thread of that supreme adventure tale. Metahistory is an approach, a preparation to recovering the thread.

Whatever the form of the original vision we seek, it must reveal the mystery of the wounding of the shaman, the single event that has so disoriented our species that we risk losing our way entirely. The discovery of the wounding is the way to overcome the pattern of abuse and domination that is now seen to propagate itself in the waves of pain spreading from the wound. That is, to heal the dominant parthology of our species.

Chickasaw poet and novelist Linda Hogan has said that “our renewal often flows from loss, pain, ashes. We are like giant redwood trees, with new life springing from our fallen selves.” (Interview with Derrick Jensen, op.cit., p. 122ff) These words express the grief that grounds the redemptive process of species-wide healing. Tree and Well together represent the power of language as instrumental to our primordial knowing, the sapience that makes us human. Linda Hogan’s comment on language might well stand as the credo for metahistory:

Story is the essential thing we have. In some ways it’s the only thing we have. Some people who want healing go to a therapist and tell the stories of their lives. Then they see the story differently, shift the pattern, and that is healing for them. In stories you have a shortcut to the world of emotion, a direct path to the mythic and unconscious. . .

Language is. It has force. Someone like N. Scott Momaday would say language is an entity, a living being. Perhaps all language is a song or a prayer. Octavio Paz wrote that when you go to the more primary ways of thinking, the word and the subject are the same thing. There is no abyss between the word and what it speaks.

Seen in this way, words have a great potential for healing, in all respects. And we have a need to learn them, to find a way to speak first the problem, the truth, against destruction, then to find a way to use language to put things back together, to live respectfully, to praise and celebrate earth, to love.

JLL: 3 Sept 2002. Revised 8 August 2007