| Site Guide |

| Tantra Tour |

| Gaian Tantra Vow |

| Foundations |

| SHAKTI CLUSTER | Dakini Calendar |

| Terma | Sierra de Libar |

The Compassion of Release

At the Cutting Edge of Dakini Instruction

At the midway point of the Vajrayogini Shift 2009, I continue to be astonished at the deft, penetrating technique of this Diamond Sky Dakini, the finesse of her cut. By this I mean that when I contemplate the primary theme of her instruction, the union of desire and compassion, I find my thoughts continually intercepted, cut down, reduced to glittering slivers of sudden illumination. I just cannot persist in thinking about desire or compassion as I formerly did: something shifts in my mind whenever I consider these two themes in unity. In fact, I am beginning to realize that much of what I previously understood about these two topics is incomplete, inadequate, distorted, or simply wrong.

Contemplation—not meditation—is central practice in the Highest Yoga Tantras. To contemplate means simply to observe the mindstream, the ordinary flow of thoughts, with attentiveness to its spontaneous self-liberating aspect. Chogyal Namkhai Norbu:

The true path of the Dzogchen practitioner is contemplation. In fact, it is only when we are in contemplation that all the tensions of body, voice, and mind are finally effortlessly released; until we discover and abide stably in this state, our experience of "relaxation" will be incomplete. Contemplation can be tied to an experience of clarity, or of bliss, but its state is one alone: the instant presence of rigpa. (The Supreme Source)

He goes on to say that contemplation in Dzogchen is the identical practice prescribed in the non-attainment techniques of Ch'an and Zen. But Dzogchen, he contends, puts a particular emphasis on the primordial state of pure, self-liberating attention, "not as 'pure emptiness' but rather as endowed with all the aspects of the self-perfection of energy."

The self-perfecting or self-liberating action of pure attention (rigpa) is present in every moment of attention, no matter how mundane, muddled, or distracted.

In the standard dakini style, Vajrayogini holds a flaying knife with a wide crescent blade, the kind used to strip the skin off the carcass of a dead animal. This is a Kaliesque implement of the charnal house. It is also the symbol of mental cutting action, the deft swipe of surgical incision into the mindstream. I have the sensation (shared now with others who are following these cycles of dakini instruction with me) that a blade slices into my heart, into my mental-emotional stance, altering my most subtle and intimate thoughts about love, attachment, desire, compassion, ego and whatever is not ego. The intervention of this Diamond Sky Dakini is vivid and palpable. She brings a bracing sense of relief and release. As I contemplate a certain situation of emotional enmeshment, I find that I simply cannot continue to think about it as before. Something shears away my troubled and confounding thoughts, leaving only a crystalline sense of detachment and elation. The finesse of Vajrayogini's blade cuts away my attachment and leaves me free to flow into release, release, release.

The instruction of Vajrayogini, now detected by others as well as myself, is clear and explicit on this essential point:

There is no release from any emotional bond without compassion.

Entrained Formulation

The above statement in bold is not a direct transcription of dakini instruction—by contrast to "You cannot become anything but more beautiful," which is. I did not think out the syntax of that poignant and pellucid statement (so I find it, anyway). It just came to me in a lightning flash, and the moment it registered in my mind I was acutely aware that it was not a production of my own mental effort. It was effortless and immediate, flashing into my mindstream with the lightning spontaneity of dakini wisdom. No so with the above statement in bold. I distinguish the naked crystalline syntax of dakini instruction from what I call entrained formulation, or instructional spinoff.

"There is no release from any emotional bond without compassion" is the syntax of John Lash, my mental and grammatical formulation, but based on what I sense to be the subtle intervention of transpersonal wisdom into my mindstream. The instruction of Vajrayogini is there, but the cut of her blade is so close to my own mental contour that I can hardly distinguish her thinking from mine. All I can do is formulate words based on the entrainment of her instruction. I conclude that to receive instruction from Vajrayogini in the pure naked spontaneity of twilight talk or subliminal syntax, I would have to maintain a level of perfect attention superior to what I can achieve at my best moments. This dakini, being as she is the supreme instructor of the Highest Yoga Tantra, requires a concomitant degree of concentration which I cannot yet reach and sustain, consistently. Thus I am reduced to communicating instructional spinoff, rather than direct instruction. So heed the language and expression in the remainder of this essay: my translation of dakini instruction, nor the direct dose.

If, at any point, what I am writing here surges into direct instruction, I will let you know. Or perhaps it will be obvious, and I won't have to....

Responsibility

How about, for the sake of discourse, we define compassion like this:

Compassion is taking responsibility for the way you treat other people. Not necessarily for the way you affect them, but the way you treat them, which may give rise to a consistent affect, corresponding to your intent, or to a converted affect, corresponding to what the other person makes of your intent.

For example, if I treat someone with the intent to make them happy, and they are happy, the affect of my behavior is consistent with the intent. On the other hand, if I treat someone with the intent to make them happy, and they respond to my action with contempt, as if I pitied them, that is a converted affect. A converted affect does not correspond to my intention for the other person. It is what they make of my behavior toward them, regardless of or even contrary to my intention. Often people say, "you make me feel so and so." This is usually the admission of a converted affect, although it may also be a true reflection of one's effect: I intend to humiliate someone by the way I treat them, and they say that they do indeed feel humiliated. That would be true effect. Generally speaking, though, the converted affect comes from the person affected, not from the treatment of the other person. It may mirror the treatment they receive, but only in a distorted way.

Converted affects can be extravagant. and extremely perverse. People can accuse you of affecting them in all kinds of ways that have nothing to do with the intention of your way of treating them. From this disturbing experience you can learn two things: either how to adjust the style and expression of your intent to achieve a consistent affect, or how to detach yourself from a reaction that does not reflect either your intent or the way you expressed it.

From this formulation of the consistency of intent and affect, I come to another principle of compassion: transparency of intent. This means that you are totally open and transparent in what you intend for another by the way you treat that individual. There is no deceit or dissimulation, no curveball action or hidden agenda. You can say exactly what you intend in the way you treat someone.

Compassion radiates in transparency of intent: allowing the best chance that the way you treat someone will be received in a consistent affect, not a contrived affect. What you give is exactly what you see the other person getting, and they know it, too.

I used to think that the mark of compassion was a disinterested view of the experience of another person: you have nothing invested in an individual, so you can offer that person pure and detached witnessing, feeling with (com-) the other's feeling, "com-passion." Now, reflecting on the union of desire and compassion, I understand that while disinterest may be a key element in compassion in some instances, more often we need to learn and express compassion with those people with whom we have something at stake. I suggest the syntax: people whom we desire something with. I want something with someone, not just from but with.

When I admit that I desire something with another person, this is the occasion to see compassion in a specific way, consistent with the instruction of Vajrayogini. This admission is the second component in the formula of release, after taking responsibility for how you treat another.

If I want something with someone else, I have an investment in that person. I used to think that compassion could not apply if there was any kind of investment at play. Now I see that it must apply even more intimately, more powerfully, in such a case. And it works both way: compassion is the attention I bring equally to what I desire with someone else, as well as what that individual desires with me. On this agreement, if can be openly stated and made into an agreement, rests the dialogue of desire.

Compassion cannot arise between two people in intimate relation without the dialogue of desire, each one admitting what s/he wants with the other. Ultimately, talk that generates compassion will be talk about the subject of compassion, framed in the situation or relationship that desire has created.

The dialogue of desire pictured in the troubadour tradition (Francesca da Rimini). The lovers are shown with a book because Renaissance aristocrats believed that literacy and high intellectual culture inspire Eros and favor both the articulation and satisfaction of desire.

This, so far, is my entrained formulation of dakini instruction from Vajrayogini on the union of desire and compassion.

The formulation continues:

In compassion, you can recognize, respect, and allow what the other person wants with you, even if you do not give that person that s/he wants. And vice versa.

Much of the horrific destruction in relationships occurs due to failed expectations, desires that are not stated and not met, wanting things that are not offered or granted. But destruction can be hugely minimized by mutual admission of what one wants from the other, with the acceptance that one may not get it. The point is, to admit it, to have the desire made known to both parties, the one who desires and the one who would grant that desire. To remain in relationship with someone who does not grant your desire might be a test of compassion, but ending a relationshp due to desire not being met can also be done with compassion. This is where the formula leads to a unique moment of truth and detachment: the release of compassion. Release is the third and final component in this formula.

Engaged Compassion

In the dialogue of desire, each individual would state in a non-demanding way what is desired with the other individual. Nothing is hidden, nothing disguised, there is no attempt to get something from someone in a covert or manipulative way. Transparency of desire leads to open admission, mutal admission. So, two points of the formula of release are clear, the second being a double-loaded point: first, responsibility for the way you treat another; second, transparency of desire and admission of what you desire with that person.

Now it gets really interesting. The question is, Once you reveal what you desire with someone, not as a demand but as a confession or invitation, and it is clearly evident that you will not have this desire satisfied—it is not the desire of the other to grant your desire, even though s/he recognizes it—what do you do? How do you release yourself in compassion from a situation where your desire is not fulfilled, not granted by the other person in the situation?

Just to contemplate the union of compassion and desire, just to hold that phrase in mind, is a remarkable exercise in mind-change. For it associates compassion, normally regarded as a transpersonal and disinterested attitude, with the most intimate and consuming of selfish emotions, desire. And it does not merely associate them: at the cutting edge of dakini instruction, with the slice of her blade laid against your heart to shear away illusion, Vajrayogini teaches that

Compassion in its highest form, in the unity of the Highest Yoga Tantra, is complementary to desire, and realized ultimately through desire, whether or not it is fulfilled.

This is an extraordinary teaching, unlike anything I have found in Buddhism, even in the unorthodox extrapolations of Tantra among, say, Lama Yeshe and Daniel Odier. It is not my teaching, the wisdom particular to John Lamb Lash, but an approximation to dakini instruction that I am now undergoing along with a few others who are currently tracking this lunar shakti from June 23 to July 22, 2009. What a releasement this is. I am humbled to be receiving this insight, and living through it in personal reality, moment by moment, as I receive it.

Last year, the Vajrayogini shift (July 4 - August 1) was attended by three momentous developments in my life: I was contacted via the site by the woman who was to become my Shakti and act as co-initiator of Planetary Tantra, I received and performed the dakini rite of addiction on Infinity Ridge, and I underwent the Ronda Moment (in that order). Reviewing that shift, I suggested that "this Diamond Sky Dakini represents a particular power of the planetary Shakti Gaia-Sophia, the focus of special clearing and healing properties of the Organic Light, of which she is a kinetic icon or animated image." What I am undergoing now attests to the clearing and healing powers of this devata in no uncertain terms.

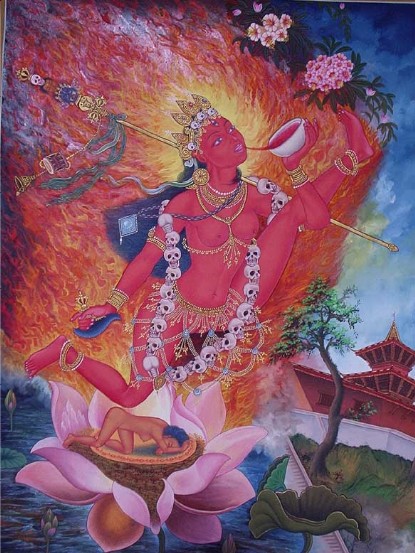

The yidam or visual icon of Vajrayogini has been depicted

in countless variations. Regardless of one's personal taste,

the received material of Hindu/Tibetan Tantra provides a

reference for connecting to the supernatural forces of the

Shakti Cluster. Over time, and soon enough, these images

will morph. The essential thing is, that they mirror the

wisdom and power within the humanity of each person.

As a practice in the Highest Yoga Tantra, Tibetan Buddhism prescribes meditation on the yidam or tutelary deity in a graphic or holographic visualization. The yidam may be a Buddha and consort in sacred intercourse (yab-yum) or a solitary dakini such as Chinnamasta the self-beheading Mahavidya, or Vajravarahi, the boar-headed manifestation of Vajrayogini. This technique derives from pre-Buddhist Dravidian cults of goddess worship centered on the erotic figure of the ista-devata, often represented by or mirrored in a real-life woman, a devadasi, tantric consort or temple courtesan (crudely, a "sacred prostitute").

The eighteen feminine deities of the Shakti Cluster are yidams or ista-devatas, radiant nodes of the Divine Feminine in imaginal form.Mere contemplation of one of these devatas, with special attention to her powers and attributes, charges and imprints the psyche with the very forces imbued in her image. The process works in the same way that an advertizing icon or corporate logo, like the MacDonald's golden arch or Nike logo, charges and imprints the psyche of consumers, compelling them not only to buy the product but to become religiously loyal to the brand!

If a cheap advertizing gimmick can do this, i.e., entrain and direct human behavior in such a potent manner, capturing and commanding the desire of the customer, imagine what a sublime supernatural imprint such as a devata of the Shakti Cluster can do.

In my experience so far, contemplation of the yidam of Vajrayogini charges the psyche with the wisdom of her specific instruction on the union of desire and compassion. This is a unique Kalika viewpoint introduced by yours truly. No Tibetan teaching comprises the element of desire in the permutating unions involving compassion, bliss, emptiness, appearance, and wisdom. But once desire is factored into the unions, compassion takes on a different look, a more inclusive scope. The deepest cut of desire touches the core of compassion. Previously, I had understood that compassion was removed from any investment in the subject of compassion. This may be so in a special, limited case of compassion. But imagine compassion that fully penetrates every relationship of desire, every conceivable bond and form of attachment to which desire gives rise. This is the compassion that gathers on the edge of Vajrayogini's blade. This is engaged compassion.

Only desire that is fully engaged in compassion can be released, allowing the liberation of the one who desires, though not of the one of whom anything is desired.

The Fourth Component

I desired something with a woman, which she did not grant me. To be released from that woman and what I desired with her, I had to find compassion in a way that was totally new to me, totally fresh and surprizing. The way I found it was extremely subtle, yet obvious. Following the instruction of Vajrayogini, I formulated the factors of responsibility, transparency, and dialogue (admission of desire)—but there was something missing. I sensed that I was still one step short of the complete formula of release. There was a fourth component.

Writing this as I live through it....

Day 19 of theVajrayogini shift. To be continued....

jll: Andalucia 11 July 2009

READ and RECORDED on March 11, 2015: NF007 Essay, on gaiaspora.org.